As a kid, I stayed up late, and I watched a lot of tv, and that particular intersection resulted in an obsession with infomercial guru Ron Popeil. I got to write about my fixation in 2018 for the first (and only) issue of a boutique-y print magazine called Sumac.

Due to the nature of these beautiful but often obscure $20 print mags, the story didn’t find the audience I was hoping for (that audience being, ideally, other people), and I really loved it, in part because I got to speak my bizarre truth and in part thanks to Susan Howson’s razor sharp editing, which she did as a favor to me, for which I paid her in flattery and empty promises.

When I started this newsletter, it was with the goal of sharing stories like this one as well as the details (awkward pitches! rambling interviews! harrowing backstory!) behind the stories and recipes I’ve written. So here it is! “Set It and Forget It,“ originally published in Sumac, May 2019.

Set it and Forget it

In the mid-nineties, I had a weird obsession, weird for a nine year old at least: Up late and unattended, I would watch any infomercial I could get my eyeballs on, and when I say watch, I mean devour, and when I say devour, I mean memorize and repeat to myself while doing boring things like riding in a car or listening to grown-ups.

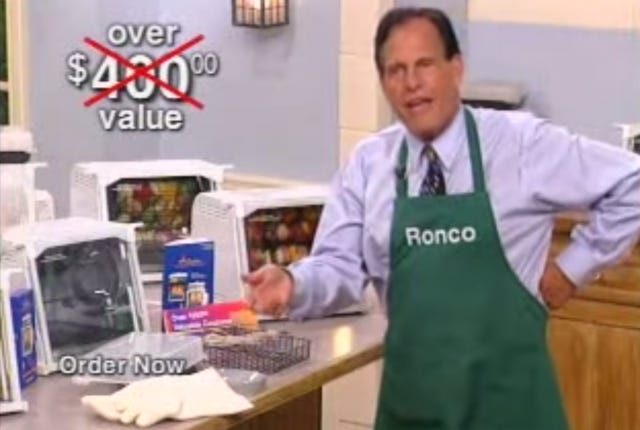

I loved their huckster charm and frantic energy, from Jose Eber’s hair extensions to Ginsu knives, but I only truly coveted the products of one infomercial svengali: Ron Popeil. He had a fatherly quality—He seemed to have all the answers, to in fact, be selling the answers for a reasonable fee. He seemed to know best.

And why shouldn’t he? In his six-decades-long career, Popeil was responsible for popularizing products like the Chop-O-Matic, Pocket Fisherman, Spray On Hair and other essential, life-bettering contraptions that could be ours for just four easy payments of $39.95. He ascended from an abandoned, impoverished youth to a celeb-elbowing millionaire on his own merits as a first-rate pitchman. He coined the phrase, “Set it and forget it,” and now, whenever someone insists, “It’s just that easy,” it’s because Ron Popeil said it first.

The first of his empire of infomercials to capture my attention was Popeil’s Automatic Pasta Maker. The claim was this: With just flour, water, egg and oil, anyone - even a kid like me - could make fresh pasta from scratch!

Popeil astonished his goofy, big-haired, puffy-sleeved buddy Nancy (our ‘everyman’ foil), the studio audience, and me with this revelation. I had never before considered the idea that pasta was something that could be made, let alone thousands varieties of it, in just three minutes. To me, pasta was born in a box and came to life in a pot of boiling water before cozying up to a ladle full of Ragu Old World Style. I didn’t know I could even want anything else.

Just a few seconds into his spiel, Popeil informs Nancy that this machine will make a mind-boggling array of pasta: Carrot pasta, spinach pasta, lemon pepper pasta, and even pastas that no one ever asked for, like Indian curry pasta and Russian borscht pasta. (It’s now a regret of mine that I never dabbled in borscht pasta). He calmly croons to the audience over the deafening whir of five pasta makers cranking out knobby noodles at once, “How many people in my audience have vegetable juice extractors at home?” Every hand goes up. Heaven help you if you have to juice your spinach in the blender like some sort of monster.

Once he’s established the variety and health benefits (you can make it with an egg - or not!), he moves on to economics. You could pay $6 on fresh pasta at the grocery store, but you’re smarter than that. You’re only going to pay $.25 to $.30 per pound for fresh pasta from now on. I had no time to do the math to realize that those prices weren’t far from normal pasta prices because math is hard and Ron Popeil hadn’t invented anything to make it easier yet.

We’re ten minutes in, and we’ve just been informed that we can actually buy this thing, the value of which is, by Popeil’s estimation somewhere around $269, give or take. “Of course you know you’re not going to pay $269,” he confides. Not with you in charge, Ron, you magnanimous bastard! Then he down-bids himself like he’s at some bizarro auction, until he says, “and you’re not even going to spend $170 on it like you may all be thinking.” It was just four easy payments of $39.99. Bless you, Ron.

Once he’s made the full pitch, he goes back for nuance, creating a clam sauce, his own one-pan wonder, right before our eyes. It looks, with the benefit of hindsight, disgusting, possibly inedible. But he plops a heap of fresh pasta in a pan full of the stuff, twirls it up and serves it to the studio audience, who bounce with applause--happy, transported, sold.

It was a kind of early culinary television with all the magic of Graham Kerr, the charisma of Paul Prudhomme, and the genius of Julia Child; and the best part was it could be MINE...if my parents said it was ok.

So, I memorized the infomercial: Ron’s part, Nancy’s part, commentary from the audience, the voice over guy. I knew if I was going to own this precious commodity, as surely I must, I was going to need to be every bit as convincing as the pitchmaster, Mr. Ron Popeil himself

And armed with this script, I began my campaign.

I started with my stepmom, Ginger: “Did you know you could make pasta from scratch in just three minutes?”

She didn’t, she murmured in acknowledgement, but nor did she seem particularly interested.

“And you can save a ton of money. Fresh pasta is so expensive if you buy it in the store! We can make it for $.25 to $.30 a pound!”

“But we don’t buy fresh pasta.”

“But fresh pasta is so healthy! You can make thousands of varieties of fresh pasta with the Popeil’s Automatic Pasta Maker! And it’s good for your cholesterol!” Admittedly, I didn’t know what cholesterol was, but this seemed to gain some traction, so I kept going: “We could be eating fresh rigatoni for dinner tonight in less time than it takes to order take out!”

Maybe that caught her attention, but I couldn’t tell. From my perspective, she just kept shaking a box of Betty Crocker mashed potatoes into boiling water like a peasant, ignoring me and doubling down her focus on the episode of Oprah she was watching.

I knew I still had work to do, so, trapped in the car with me, my Dad became my next unwitting audience. I unloaded a few choice lines from the script on him. But other than maybe a slightly amused face in the rearview, I got no farther than I did with Ginger. This went on for the better part of the summer and into the fall. By the time November rolled around, they knew as much of the script as I did, but they had given no indication whatsoever that it had motivated them to break free of their typical thirty-minute dinner shackles in favor of what was clearly faster, healthier and, let’s not forget, a huge financial savings.

But at some point, Dad and Ginger must have talked the whole thing out. They swapped stories after my bedtime and realized that they would never shut me up without forking over $160 plus shipping and handling on the thing and calling it a Christmas present, and that’s exactly what they did.

When I opened up a large, lone box that Christmas morning, I realized: THIS is why they call it Christmas morning! This thrill may never be matched again. And here I am, nine years old, extruding noodles like a real chef on my proto-Arco Baleno. Wouldn’t Papa Popeil be so proud of me? I knew that he would.

The pasta is a vague memory now, eclipsed by the pure pleasure of owning the machine itself. I can just barely recall a slightly gummy, completely unremarkable pasta that, you guessed it, cozied up to a ladle full of Ragu Old World Style because that’s just what pasta did back then, no matter what you may have heard about something called ‘clam sauce.’

I only ever used my prize once. That was enough to satisfy whatever yearning I had. It took up an ungodly amount of space in the cabinets for six months and then went to live the rest of its undignified life in the basement where it collected mouse turds and looked at us accusingly whenever we went down there looking for something else.

But, as they say in the world of infomercials, that’s not all. Essentially satisfied by the acquisition of the pasta maker, it was time to set my sights on a new prize: The Ronco Electric Food Dehydrator. At this point, I was closer to 11 or 12, and I had shrewdly identified that my stepmother was as big of a mark as I was. I wouldn’t need to memorize anything this time. I’d just have to time things right, get her in front of the tv around 11:00 pm, and Ron Popeil would handle the rest.

And of course he did. We became the proud new owners of a food dehydrator. We could dehydrate fruit and put it in our own homemade trail mix! We could start hiking trails! We could suck the life out of beef tenderloin and produce our own leathery jerky! You know, for the trails.

And so we did make beef jerky, and it was addictive and savory and chewy and wonderful. Ginger made three or four gallon-sized bags of it, which if you stop and think about it, is an insane amount of jerky for any group of humans not embarking on a months-long trek into the wilderness. So, in our own kind of epic adventure, the family packed up our minivan and headed from Roanoke, Virginia to Charlotte, North Carolina for a Jimmy Buffet concert, with jerky as our fuel.

We ate it all. Even after we knew it was a bad decision, we kept going back for bag after bag of the stuff. We harnessed our meat sweats, set up our camping chairs, and for the better part of Buffet, we took turns scurrying to Blockbuster Pavilion’s porta potties to shit our brains out. This is probably why we don’t do the whole ‘trail’ thing in my family. We get it really wrong. That was the last time we ever used the Ronco Electric Food Dehydrator, and it too was relegated to life in the basement.

But, while his inventions went on to lead lonely lives next to the treadmill and the typewriter, Popeil’s work was done: He had inspired in me a love of culinary showmanship and the vague idea that I could make food--from fresh pasta to dried meat--for myself, with or without the assistance of gadgets. It was just that easy, and I was hooked.